Last week I sat down with Iimura Kazuki (飯村一樹) at Ginza Farm, with a translator, and learned much more about his ideas for Ginza Farm, his background and his next project.

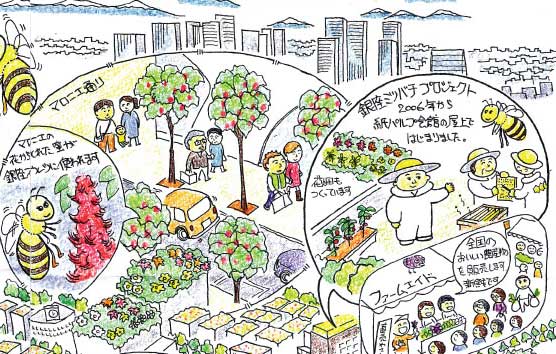

Iimura-san told me that he is very interested in urban farming in Japan and worldwide. His background has given him unique skills for pulling off something that at first seems impossible: creating a ground level rice farm in one of Tokyo’s most expensive neighborhoods.

Iimura-san recently worked with rural towns on revitalizing their small commercial streets, most recently in Shizoka. He realized that this local problem required new connections with the rest of the world. When he turned his attention to Tokyo farming, he drew on Ginza connections he forged as a venture capitalist. And finally his obvious skill with growing comes from his childhood on his parents’ farm in Shimoutsuba in Ibaraki prefecture, a town known for its high quality rice. The Ginza Farm soil and rice come from his parents’ farm.

How did Iimura-san secure a site that is on a small side street west and north of the intersection of Chuo Dori and Yanagi Dori (not far from the twisty De Beers building)? Using connections with tax accountants and attorneys, he located the plot and spent six months negotiating with the landlord. Although I do not know the details, apparently lending land between demolition and construction confers some significant tax advantages, yet still it took a long process of negotiation.

A giant photo banner at the back of the field proclaims that “One hundred rice farmers make Japan healthy.” Below is information about the supporting farms. Iimura-san contacted some of Japan’s most award-winning farms, appealing to their pride and patriotism. He spent two months sending documents and gaining equal support from these farmers.

Some of the activities at Ginza Farm have included a farmer’s market, a Tanabata festival with Nagashi Somen (noodle rolling along a long bamboo tube). At the festival, he said that the kids who participated were initially afraid of getting dirty, but that within five minutes they were throwing mud and “becoming monsters.” He wonders if it might have been the first time for many of these city kids to play in the dirt.

The field, the sitting area of benches and tables, the awning are all very rustic and well crafted. Iimura-san told us that a famous bamboo artist and his workers built much of it.

Iimura-san said that many types of people have visited. With the introduction of the ducklings, more women have become interested. I noticed an interesting mix of Ginza workers, including construction workers and shop clerks. Iimura-san explained that the school kids who helped plant the farm each received a plant to take home. Iimura-san was very proud that one kid came back to tell him that the rice he cared for was bigger and stronger than the Ginza Farm’s.

A true farmer, Iimura-san told me of very specific growing problems in Ginza that makes it hard to grow rice well. The sun does not shine into the field until 9 am which is bad. At night, the field is full of artificial light, which he has attempted to control with a large black plastic curtain he closes at dusk. “It’s important for the rice to sleep.” And finally, the night time temperature in Ginza is too warm, without the cool breezes found in the countryside.

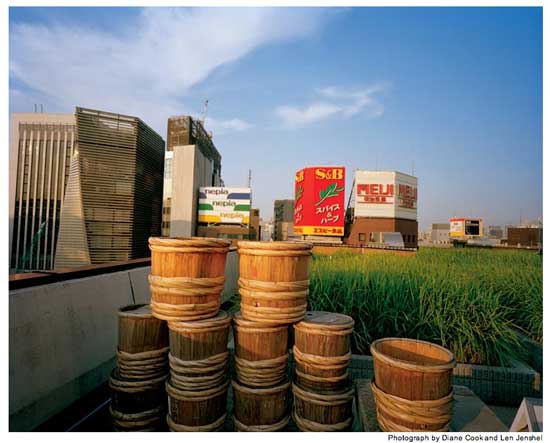

Iimura-san has many future plans: to create another Ginza Farm next year, to find new markets for Japanese rice, and to open a rental farm (貸し農園) with sixteen roof top plots on the top of the Paul Smith building in Omotesando. He says the rental farm has wonderful views of Roppongi and Tokyo.

Iimura-san’s resourcefulness and passion will be very helpful, and I am looking forward to visiting Ginza Farm again and his next projects.

The photo at the top of the post and below show how the rice and the ducklings have grown so much within 10 days. While my last visit he showed me a tiny frog, this time he pointed out a small snail on the trunk of the entrance-way maple tree.