What if an urban forest is being built in Tokyo and no one knows?

In the past weeks, I have met with a Tokyo Metropolitan planner, the Mori Building press department, a foreign real estate developer, a University of Tokyo environmental scientist, a clean energy entrepreneur, and a visiting artist-in-residence working on urban farming. In the next days, I’ll also be meeting with a Tokyo architect and a senior Hitachi representative.

At this early stage in my project, one thing that has become clear is how little known some of Tokyo’s most innovative projects are among real estate professionals, cultural leaders and ordinary citizens. I have been surprised how few people in Tokyo know about Ando Tadao’s plan to create a forest in the sea, called Umi no mori, with half a million trees built over 88 hectares of landfill in the Tokyo bay.

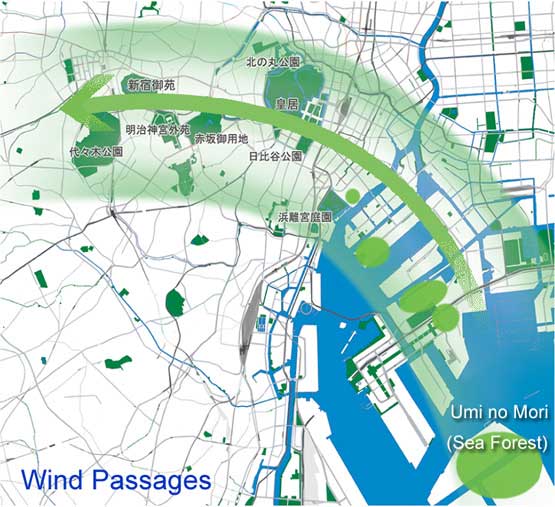

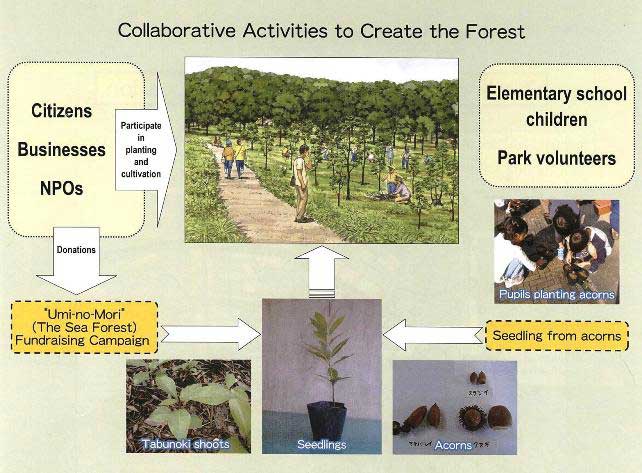

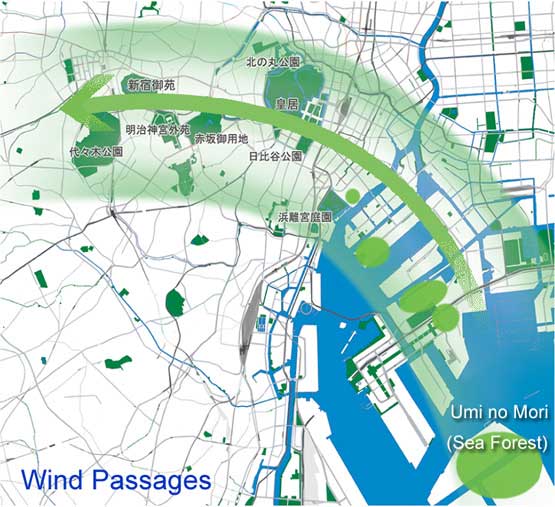

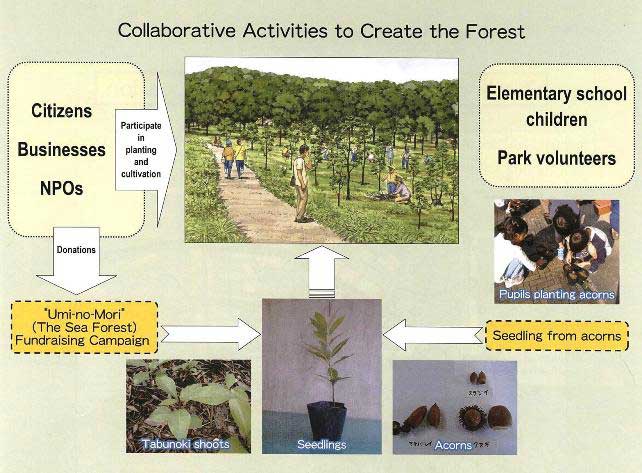

Initiated in 2007 as part of the ten year plan to re-make the city in part to compete for the 2016 Olympics, this Sea Forest project aims to clean the city’s air, reduce the heat island effect, involve elementary school children, and provide cool breezes throughout the city in summer.

The land is built on top of 12.3 million tons of municipal waste buried from 1973 to 1987, topped with alternating layers of refuse and cover soil, originating at no cost from water purification plants, sewage sludge, city park and street tree compost.

There are also ambitious plans to involve elementary school children with growing seedlings and planting them in the new forest.

And here’s Tado Ando’s inspiring message about this project’s importance for Tokyo and the world’s connection with the environment:

Umi-no-Mori ( Sea Forest) will become a symbol of our recycling-oriented society through which Japan, a country that has a tradition of living hand-in-hand with nature, can make an appeal to the world about the importance of living in harmony with the environment. In view of the fact that landfills exist in all corners of the world, I perceive this island as a forest that belongs not just to Tokyo, but to the world, and through this project, wish to communicate the message of “living in harmony with nature.”

「海の森」は東京の森ではなく地球の森として、世界へ向けて、「自然とともに生きる」というメッセージを届けることができると考えています。かつて焼け野原になった街・東京は、先人たちの努力によって復興されました。今度は私たちの手で緑豊かな森をつくり、次世代の子供たちに美しい自然を愛でる心を伝えたいと考えています。未来の東京、日本そして地球のために、皆さん一人一人の「志」をどうか募金に託してください。

Perhaps the Tokyo government does not want to spend too much money on publicizing their activities, with the idea that it’s better to act than talk. However, this enormous public work project seems like a great opportunity to educate Tokyo residents and the world about the positive activities city governments are taking on behalf of people and the environment.

To read more about Umi no Mori:

http://www.uminomori.metro.tokyo.jp/index_e.html (English)

http://www.uminomori.metro.tokyo.jp/index.html (日本語)